(Ever wonder why we eat dried fruit on Tu b’Shvat? — apparently, it’s complicated).

The Torah believes that in trees, we find life, — even though to us, it appears as if time and circumstances (planted-ness) are arrayed against us.

Of course, Western Literature has traditionally understood the forest or the woods, while full of life, are seen as dangerous and frightening: Oh my.

See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u-YcDlb9Y2M

Trees appear early on in the Torah — often as markers in time — and importantly for our understanding, they appear on the horizon — on our way from here to “there” — what do you suppose they presage? Could it be life renewed?

כה וַיִּצְעַק אֶל-יְהוָה, וַיּוֹרֵהוּ יְהוָה עֵץ, וַיַּשְׁלֵךְ אֶל-הַמַּיִם, וַיִּמְתְּקוּ הַמָּיִם; שָׁם שָׂם לוֹ חֹק וּמִשְׁפָּט, וְשָׁם נִסָּהוּ. |

Ex 15: 25 And he cried unto the LORD, and the LORD showed him a tree, and he cast it into the waters, and the waters were made sweet. There He made for them a statute and an ordinance, and there He proved them; |

| כו וַיֹּאמֶר אִם-שָׁמוֹעַ תִּשְׁמַע לְקוֹל יְהוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ, וְהַיָּשָׁר בְּעֵינָיו תַּעֲשֶׂה, וְהַאֲזַנְתָּ לְמִצְותָיו, וְשָׁמַרְתָּ כָּל-חֻקָּיו–כָּל-הַמַּחֲלָה אֲשֶׁר-שַׂמְתִּי בְמִצְרַיִם, לֹא-אָשִׂים עָלֶיךָ, כִּי אֲנִי יְהוָה, רֹפְאֶךָ. {ס} | 26 and He said: ‘If thou wilt diligently hearken to the voice of the LORD thy God, and wilt do that which is right in His eyes, and wilt give ear to His commandments, and keep all His statutes, I will put none of the diseases upon thee, which I have put upon the Egyptians (i.e. Death Central); for I am the LORD that healeth thee.’ {S} |

| כז וַיָּבֹאוּ אֵילִמָה–וְשָׁם שְׁתֵּים עֶשְׂרֵה עֵינֹת מַיִם, וְשִׁבְעִים תְּמָרִים; וַיַּחֲנוּ-שָׁם, עַל-הַמָּיִם. | 27 And they came to Elim, where were twelve springs of water, and three score and ten palm-trees; and they encamped there by the waters. |

Many centuries later, when Mark Twain visited the Land of Israel, he called it “a hopeless land.” He even mentioned there were few if any people there and ‘nary a tree in sight.’

Note the language chosen by Twain—”a hopeless land.” By design or not, his words corresponded with the prophet of the Babylonian exile, Ezekiel. The Jewish exiles of the first half of the sixth century BCE were unfamiliar with the historical patterns of exile and redemption we often speak about: also known as deportation and return. They looked around them and saw how, after a generation or two, every people whose country had been destroyed, or assimilated into the Babylonian population where they had been exiled, and concluded that their fate would be the same. The Prophet Ezekiel articulated what the people were saying out loud: “Our bones are dried up and our hope is gone; we are cut off.”

____________

The bottom line for our examination,

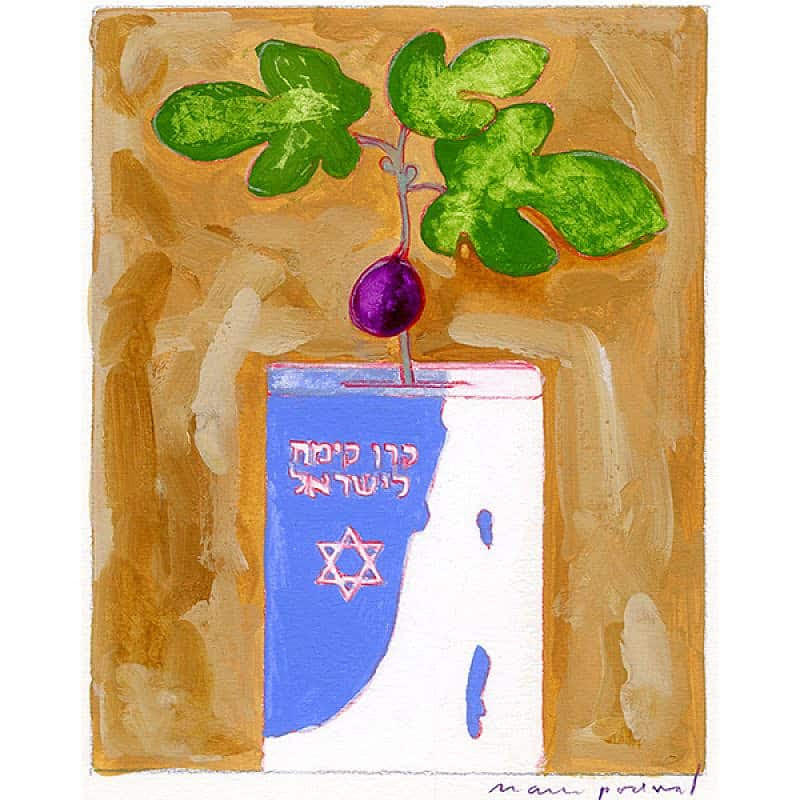

The People of Israel understood that being replanted in the Land of Israel is a sign of Hope — which is reflected in Hatikva (Note: ‘tikva,’ meaning ingathering — also means hope).

Let’s take a closer look at the wording of the Hatkiva:

“Od Lo Avda Tikvatenu” or “We Have Not Yet Lost Our Hope”

(this ^ is influenced by Ezekiel 37:11 cited directly below):

Is our Hope — dried up?

(Ever wonder why we eat dried fruit on Tu b’Shvat?)