Leopoldstadt?

Vienna, Austria or the world — a place of modernity, of culture and of refinement . . . .

Historical fact: Vienna and all of Austria welcomed the Germans as liberators — later only to claim themselves, as Austrians, to be victims. — Just a moment’s throw from Auschwitz

Austria today remains laced with racist antisemites — and they are not unique to this phenomenon.

Historical fact: deadly antisemitism is not dead . . . (and neither are the Jews).

“The next year, when he went to Prague for a PEN conference and to see his friend, President Václav Havel, he visited the synagogue where the names of his grandparents were inscribed as Holocaust victims.The next year, when he went to Prague for a PEN conference and to see his friend, President Václav Havel, he visited the synagogue where the names of his grandparents were inscribed as Holocaust victims.”

Leopoldstadt: Even without any overt violence, the Kristallnacht scene, with its shiny blond monster calling the Jewish children a “litter,” is thus brutal, wiping away all the beauty in seconds. But the play’s argument and its likely source in Stoppard’s own life does not really emerge until the scene that follows, set in 1955. It is then, as Vienna prepares to open its new postwar opera house with an ex-Nazi on the podium, that we are explicitly asked to consider the connected problems of historical memory and premonition. Is it a corollary of the warning that we must never forget the Holocaust that we must always expect it again? (https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/02/theater/leopoldstadt-review.html?searchResultPosition=5)

Gd: “All those who wanted you dead, are now dead.”

- I am not sure Moses believed him — so then how frightening would it have been for Moses to go back to Egypt? (Ex 4:19)

- Does Stoppard go back to Vienna — do any of us?

- Is a trip to Auschwitz for the Eastern European Jew, a March of the Living?

- A march of regret, or perhaps a statement, are we not a bit late?

| יט וַיֹּאמֶר יְהוָה אֶל-מֹשֶׁה בְּמִדְיָן, לֵךְ שֻׁב מִצְרָיִם: כִּי-מֵתוּ, כָּל-הָאֲנָשִׁים, הַמְבַקְשִׁים, אֶת-נַפְשֶׁךָ. | Ex 4:19 And the LORD said unto Moses in Midian: ‘Go, return into Egypt; for all the men are dead that sought thy life.’ |

The play: Leopoldstadt / The author: Sir Tom Stoppard / The audience: Us

DORSET, England — Long before he became the august Sir Tom Stoppard . . .

Tomas fell in love with all things English and followed his mother’s lead in not looking back. She played down her history and Jewishness, thinking she had delivered her boys to safe harbor.

The cascading escapes made Stoppard feel as though he had “this charmed life.”

“I was scooped up out of the world of the Nazis,” he said. “I was scooped up out of the way of the Japanese, when women and children were put on boats as we were being bombed. I was just put down in India where there was no war. The war ended, my mother married a British army officer and so instead of ending up back in Czechoslovakia in time for Communism — they took over in 1948 when I was 11 — here I was, turned into a privileged boarding-school boy. I was just going on, saying ‘Lucky me.’”

________

In 1993, a cousin, Sarka Gauglitz, who lived in Germany, got in touch. She came to the National Theater in London for lunch to talk to him and his mother about their Jewish family history.

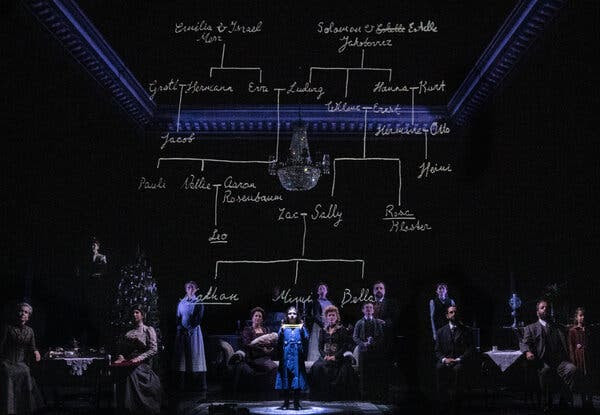

“There was this weird scene where I said to Sarka, ‘How Jewish are we?’ and then she said, ‘What? You’re Jewish.’ I said, ‘Yes, yes.’ I was embarrassed. So I’m kind of going, ‘Yes, I know I’m Jewish, but how?’ So she then drew this family tree.”

She told him how his four grandparents had perished at the hands of the Nazis and how his mother’s three sisters had died in Auschwitz and another camp — a horrific litany that is echoed in “Leopoldstadt.”

“I was totally poleaxed,” he said. “I was in my 50s. I’d had this entire life. I couldn’t change it retroactively even in my mind. So it wasn’t like some kind of new start. I just carried on being the person I was.”

The next year, when he went to Prague for a PEN conference and to see his friend, President Václav Havel, he visited the synagogue where the names of his grandparents were inscribed as Holocaust victims.

After years of living “as if without history,” the playwright belatedly reckons with his Jewish roots, and his guilt, in “Leopoldstadt,” his most autobiographical play.

My note: It ends with the names of his family who neither understood nor recognized their Jewish identity and yet they die, because they are Jewish, at Auschwitz — intensely sobering. Tune in . . .