Here we have something we have not seen before, we have ‘a man given a plan and a blessing.’ But before we begin to extol the great blessing bestowed upon our new(ist) hero Abraham, let us at the very least understand the context in which he emerges.

We have spent an inordinate amount of time discussing the relationship between Noah and Gd as described in Chapter Six of Genesis.

First we have this: –>

ח וְנֹחַ, מָצָא חֵן בְּעֵינֵי יְהוָה. {פ} |

8 But Noah found grace in the eyes of the LORD. {P} |

| ט אֵלֶּה, תּוֹלְדֹת נֹחַ–נֹחַ אִישׁ צַדִּיק תָּמִים הָיָה, בְּדֹרֹתָיו: אֶת-הָאֱלֹהִים, הִתְהַלֶּךְ-נֹחַ. | 9 These are the generations of Noah. Noah was in his generations a man righteous and whole-hearted; Noah walked with God. |

We discussed the plans that Gd had for humanity – difficult, as they were to understand. Along with those plans were the instructions given to Noah to build an Ark (a Teva with kopher or pitch to safeguard those within). For the record, let’s remember Noah’s response to Gd’s instruction. He does what he is told and says not a word otherwise.

The March of Abraham, painting by József Molnár, 19th century

Now, let us return to Abraham. Yes, he does leave his homeland at the request, or should we say, the instruction by Gd to go ‘to a land that I will show you.’ In case you didn’t notice it, these are the very words of the Debbie Friedman song, which makes us cry at almost every Bar or Bat Mitzvah candle-lighting-ceremony that we can remember . . .

Lyrics

L’chi lach, to a land that I will show you

Leich l’cha, to a place you do not know

L’chi lach, on your journey I will bless you

And (you shall be a blessing) l’chi lach

And (you shall be a blessing) l’chi lach

And (you shall be a blessing) l’chi lach

L’chi lach, and I shall make your name great

Leich l’cha, and all shall praise your name

L’chi lach, to the place that I will show you

l’chi lach

(L’sim-chat cha-yim) l’chi lach

(L’sim-chat cha-yim) l’chi lach

And just in case you find yourself singing along with these lyrics, and if you feel like walking down memory lane — then here is a video recording of Lechi Lach.

And here, within the Torah itself, is its inspiration . . .

Genesis Chapter 12 בְּרֵאשִׁית

| א וַיֹּאמֶר יְהוָה אֶל-אַבְרָם, לֶךְ-לְךָ מֵאַרְצְךָ וּמִמּוֹלַדְתְּךָ וּמִבֵּית אָבִיךָ, אֶל-הָאָרֶץ, אֲשֶׁר אַרְאֶךָּ. | 1 Now the LORD said unto Abram: ‘Get thee out of thy country, and from thy kindred, and from thy father’s house, unto the land that I will show thee. |

| ב וְאֶעֶשְׂךָ, לְגוֹי גָּדוֹל, וַאֲבָרֶכְךָ, וַאֲגַדְּלָה שְׁמֶךָ; וֶהְיֵה, בְּרָכָה. | 2 And I will make of thee a great nation, and I will bless thee, and make thy name great; and be thou a blessing. |

| ג וַאֲבָרְכָה, מְבָרְכֶיךָ, וּמְקַלֶּלְךָ, אָאֹר; וְנִבְרְכוּ בְךָ, כֹּל מִשְׁפְּחֹת הָאֲדָמָה. | 3 And I will bless them that bless thee, and him that curseth thee will I curse; and in thee shall all the families of the earth be blessed.’ |

Here’s a link to the Barnes which shows a little of what I am referring to:

We are often given to comparing all sorts of things. In our discussions I have often referred everyone to the Barnes Museum, or at the very least, given the times in which we live, to their website. You will see objects that Barnes himself chose to place in close proximity to the various paintings that he managed to accumulate over a lifetime and his choices rarely reflected a motif such as we might find in other collections or museums. It was his practice to place disparate objects alongside (or on top) of his paintings because in doing so, he meant to evince not just a comparison of the paintings and objects, but very possibly a reaction that we may never have thought of before.

We too have seen this in our own class discussions, especially when we have placed alongside our Torah readings selected selections from the Prophets, selections we call ‘Haftaras.’

And just as an additional Haftara reading placed alongside of the Torah will cause us to compare and draw something out we may not have noticed earlier, so too we will see this within the Torah when we look (now) at Abraham.

Of course we have talked about being ‘the Children of Noah,’ or more simply, of ‘Humanity’ as we know it. But as discussed, we are called the Children of Abraham because it is Abraham who learns something that Noah was incapable of learning.

Abraham learns a certain willingness to speak up and at times to defy Gd. Of course there are problems with this understanding. Abraham does have his deficiencies – of this we are clear. In one example, when he and Sarai are in the process of sojourning (i.e. in a somewhat extended visit). Abraham, in order to save his own life, instructs Sarai to lie and say that they are brother and sister.

יא וַיְהִי, כַּאֲשֶׁר הִקְרִיב לָבוֹא מִצְרָיְמָה; וַיֹּאמֶר, אֶל-שָׂרַי אִשְׁתּוֹ, הִנֵּה-נָא יָדַעְתִּי, כִּי אִשָּׁה יְפַת-מַרְאֶה אָתְּ. |

Gn 12:11 And it came to pass, when he was come near to enter into Egypt, that he said unto Sarai his wife: ‘Behold now, I know that thou art a fair woman to look upon. |

| יב וְהָיָה, כִּי-יִרְאוּ אֹתָךְ הַמִּצְרִים, וְאָמְרוּ, אִשְׁתּוֹ זֹאת; וְהָרְגוּ אֹתִי, וְאֹתָךְ יְחַיּוּ. | 12 And it will come to pass, when the Egyptians shall see thee, that they will say: This is his wife; and they will kill me, but thee they will keep alive. |

| יג אִמְרִי-נָא, אֲחֹתִי אָתְּ–לְמַעַן יִיטַב-לִי בַעֲבוּרֵךְ, וְחָיְתָה נַפְשִׁי בִּגְלָלֵךְ. | 13 Say, I pray thee, thou art my sister; that it may be well with me for thy sake, and that my soul may live because of thee.’ |

And yes, you probably could have seen this coming. Things really do not go well for him, or for Sarai or for that matter, the quality of their Egyptian vacation.

יז וַיְנַגַּע יְהוָה אֶת-פַּרְעֹה נְגָעִים גְּדֹלִים, וְאֶת-בֵּיתוֹ, עַל-דְּבַר שָׂרַי, אֵשֶׁת אַבְרָם. |

Gn 12:17 And the LORD plagued Pharaoh and his house with great plagues because of Sarai Abram’s wife. |

| יח וַיִּקְרָא פַרְעֹה, לְאַבְרָם, וַיֹּאמֶר, מַה-זֹּאת עָשִׂיתָ לִּי; לָמָּה לֹא-הִגַּדְתָּ לִּי, כִּי אִשְׁתְּךָ הִוא. | 18 Pharaoh called Abram, and said:’What is this that you have done to me, why did you not tell me that she was your wife? |

| יט לָמָה אָמַרְתָּ אֲחֹתִי הִוא, וָאֶקַּח אֹתָהּ לִי לְאִשָּׁה; וְעַתָּה, הִנֵּה אִשְׁתְּךָ קַח וָלֵךְ. | 19 Why said you: She is my sister, so that I took her to be my wife; now take your wife and be on your way.’ |

While it is true that Abraham is a man of action, it is equally true that his actions are not always appropriate, even in his own time. We, in our time, will try to make sense of his actions, and even justify them. We have an almost fetish-like tendency to explain all of this from ‘the comfortable seat of the morality of our own times.’

The more important truth is that the Torah never seeks to glorify our ancestors; on the contrary, to recognize their faults, as illustrated, can often lead to invaluable lessons, even for us.

These lessons are often in the comparisons that these stories bring out when placed alongside of each other (i.e. many of our Haftarot alongside the Torah readings).

Sometimes these comparisons are internal, such as the comparisons we make of Noah and Abraham.

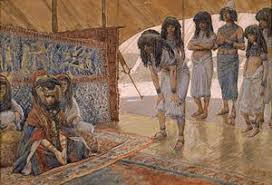

Here below is an example of Sarah’s harsh treatment of Hagar, which makes many of us uncomfortable. We wince when we learn of the way in which Hagar and Ishmael are cast out (and flee from, like refugees), especially as we watch the child lying famished, on the verge of dying.

We are even more uncomfortable when we see that Abraham has an almost hands off and callous reaction to Sarah’s envy and tells her that she may do as she wishes with the Handmaid, almost as if she has no rights, ‘a refugee taken in’ and then just as casually ‘cast off’ like a dust rag, along with her almost illegitimate son.

| ג וַתִּקַּח שָׂרַי אֵשֶׁת-אַבְרָם, אֶת-הָגָר הַמִּצְרִית שִׁפְחָתָהּ, מִקֵּץ עֶשֶׂר שָׁנִים, לְשֶׁבֶת אַבְרָם בְּאֶרֶץ כְּנָעַן; וַתִּתֵּן אֹתָהּ לְאַבְרָם אִישָׁהּ, לוֹ לְאִשָּׁה. | 3 And Sarai Abram’s wife took Hagar the Egyptian, her handmaid, after Abram had dwelt ten years in the land of Canaan, and gave her to Abram her husband to be his wife. |

| ד וַיָּבֹא אֶל-הָגָר, וַתַּהַר; וַתֵּרֶא כִּי הָרָתָה, וַתֵּקַל גְּבִרְתָּהּ בְּעֵינֶיהָ. | 4 And he went in unto Hagar, and she conceived; and when she saw that she had conceived, her mistress was despised in her eyes. |

| ה וַתֹּאמֶר שָׂרַי אֶל-אַבְרָם, חֲמָסִי עָלֶיךָ–אָנֹכִי נָתַתִּי שִׁפְחָתִי בְּחֵיקֶךָ, וַתֵּרֶא כִּי הָרָתָה וָאֵקַל בְּעֵינֶיהָ; יִשְׁפֹּט יְהוָה, בֵּינִי וּבֵינֶיךָ. | 5 And Sarai said unto Abram: ‘My wrong be upon thee: I gave my handmaid into thy bosom; and when she saw that she had conceived, I was despised in her eyes: the LORD judge between me and thee.’ |

| ו וַיֹּאמֶר אַבְרָם אֶל-שָׂרַי, הִנֵּה שִׁפְחָתֵךְ בְּיָדֵךְ–עֲשִׂי-לָהּ, הַטּוֹב בְּעֵינָיִךְ; וַתְּעַנֶּהָ שָׂרַי, וַתִּבְרַח מִפָּנֶיהָ. | 6 But Abram said unto Sarai: ‘Behold, thy maid is in thy hand; do to her that which is good in thine eyes.’ And Sarai dealt harshly with her, and she fled from her face. |

It doesn’t take much to see Abraham as equally culpable. Nor is it difficult to see Abraham as a flawed human being – who not unlike his ancestor Noah, is evolving, to and fro.

Of course, this story in which we read of Abraham rising early, without any hesitation, in order to answer the call of Gd to sacrifice his son is now just as problematic, if not more so.

| ב וַיֹּאמֶר קַח-נָא אֶת-בִּנְךָ אֶת-יְחִידְךָ אֲשֶׁר-אָהַבְתָּ, אֶת-יִצְחָק, וְלֶךְ-לְךָ, אֶל-אֶרֶץ הַמֹּרִיָּה; וְהַעֲלֵהוּ שָׁם, לְעֹלָה, עַל אַחַד הֶהָרִים, אֲשֶׁר אֹמַר אֵלֶיךָ. | 2 And Gd said: ‘Take now thy son, thine only son, whom thou lovest, even Isaac, and get thee into the land of Moriah; and offer him there for a burnt-offering upon one of the mountains which I will tell thee of.’ |

Who among us can understand this, unless of course, like the great philosopher Soren Kierkegaard, we would understand Abraham as so filled with faith and in awe of Gd, that to Kierkegaard, Abraham has become the true (albeit lonely), Knight of Faith and the story is really about the love of Gd over and above the love of one’s child. This is problematic and his flaws are now, to our sensitivities, just too great to bear.

In our upcoming class gathering, let’s take a look at a story, encased in a Haftarah (an enigma wrapped in conundrum) and ever so angrily placed alongside the Torah in which we read of Sarah’s death.

Note: remember the arrangement of the objects in the Barnes museum, and also remember that we have a tendency to compare things when they are placed side by side, in this case, perhaps it is in order to give a voice to that which is yet unheard, the ‘Voice of Sarah’ before she dies.

The Haftarah, the Prophetic reading, tells us of a woman who has lost her child and she acts with a certain fury, one aimed at the Man of Gd who she indicts with a righteous-anger-like -indignation, so much so that the the Man of Gd makes a decision (almost unheard of) to bring the child back to life.

The Sages, חז׳׳ל, like Barnes himself, (l’havdil) made a decision to place these two stories side by side, pushing us to see not only the relationship of one woman’s grief to another, but a relationship in which one dies of shock, powerless in her near-grief to say or to do anything, but only to die of shock. And the other woman we see now rises up in a powerful indignation and indict everyone culpable of having had any part of this . . . and that would lead us, especially in this case, to turn our eye to our good and flawed friend, Abraham.

—- Here’s a note to ponder: It is true that our friend and ancestor Noah curses his progeny. But we should also note, when Noah makes a sacrifice soon thereafter (one that we have discussed in great detail), it is not his son who he chooses as his sacrifice. —-

In closing, we can see that although Abraham is deficient, flawed as it were, still it is he who has taken his child, the next generation, off the altar, and unlike Noah, it is without a curse.

We, in our own times, must learn from his deficiencies — and if we are up to the challenge, we too can benefit from his blessings, the very same blessings with which we began this contrast — between Noah and Abraham.